” The invisible labor required to forge communities in a pandemic, the tenacity to reckon with the climate crisis blazing right outside our doors – just part of the job, we say. The world keeps turning. And so we do, too. Until we can’t.”

Mid-meeting, someone asks me a question, and I blank out for a few moments before fumbling out, “Sorry – brain fog.” Empathetic nods from every corner of the Zoom call, a few laughs. My teammates understand; they’ve been feeling it, too.

If you’re working in the development sector, you probably know what I mean. While everyone reacts to burnout differently, we often share the same symptoms: a gray sluggishness, a distinct lack of our usual sharpness, any and all creativity swirling down the drain.

After working until 1am (and on the weekends) for a beloved startup, our co-executive director Angeli Recella describes her past experience with burnout as a chipping away of her sense of self. “I literally couldn’t find the “right” words to tell people about who I am and what I do without mentioning the organization,” she writes. “So much so that when I did decide to leave, I had a sinking feeling – like I was sucked into the earth and then suddenly a vacuum of nothingness. I felt lost without it.” Relatable yet?

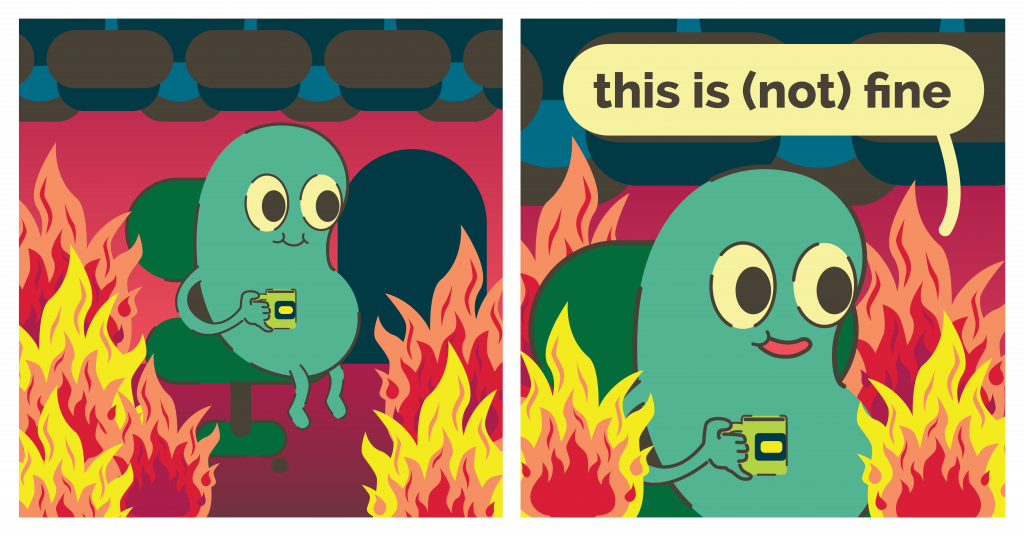

But it’s not like we can help it – right? This is what we signed up for, when we said we wanted careers that made sense: to be elbows-deep in shadow work. The invisible labor required to forge communities in a pandemic, the tenacity to reckon with the climate crisis blazing right outside our doors – just part of the job, we say. The world keeps turning. And so we do, too. Until we can’t.

In an article written in 2014, long before “Filipino resilience” was booted out as a positive ideal in the national consciousness, Shakira Sison describes our poor attempts at dealing with pain: “We rush past discomfort and onto acceptance as quickly as possible. We want to turn the negative into a positive all at once without much thought. This is an admirable trait to have, to be culturally independent and self-reliant, to focus on positive, productive actions. Pinoys do not dwell. We simply move on.”

And move on, we do. Admittedly, I’m one of those Pinoys. Raised to be happy happy lang, I was taught to grin and bear it. To get by on my own strength, if not sheer stubbornness. I see traces of it everywhere: in my friends who’d rather drop dead than file a mental health leave; in the community pantries we’ve built because ayuda is not enough; in the hordes of COVID-19 survivors walking around with unaddressed PTSD, expected to keep studying, keep working, like nothing happened, like this is all just regular fare.

Instead of pausing to heal, we soldier on. We make lists, turn to productivity trackers. Set “pandemic goals” for ourselves. “What’ve you done?” we ask one other, as if grieving under the shadow of unprecedented loss is no longer enough. We cling to the hustle.

Perhaps, this too, is another symptom. Sophy Banks, in a conversation with Boundless Roots members on health and trauma, shares, “When we are traumatised, our nervous system is not functioning correctly. On a collective level, that means society is organising itself more from place of fight, flight and freeze — perhaps also appeasing or dissociating.”

Are we dissociating? I have many reasons to think so. Our happy happy culture has failed us, and we don’t know how to act.

Worse: we’ve forgotten how to grieve.

” I believe our reaction to burnout is a symptom that we’ve lived too long in a system designed for collapse, a system that does not feel the pain that it is causing. “

Burnout and the system

If our knee-jerk reaction to pain is to withdraw – which is not only unkind, but unsustainable – how do we reprogram bad habits?

First, it’s almost impossible to understand burnout and trauma without talking about its engine. Our patterns of addressing burnout at home and at work are always linked to what the broader culture dictates – the “system” as we call it. And like any mechanism, these instructions are often invisible if you don’t know where to look. Staci Haynes explains, “People often develop prominent strategies for survival, safety, belonging, and dignity. While these reactions are automatic and stored deep in the body, they are also shaped by culture, gender, class, etc. Fundamentally, we hold these survival reactions and adaptations as wise, intelligent, and essential.”

I believe our reaction to burnout (or non-reaction) is a symptom that we’ve lived too long in a system designed for collapse, a system that does not feel the pain that it is causing, be it ecological damage or psychological. Simply put: it is important to take notice when we are burned out, so we can heal ourselves, our organizations, and continue to show up and do the work. We need to shake off the cobwebs and question why we do the things we do when we are in pain.

Perhaps it’s useful to think about the hidden taboos around mental health that exist in our culture. What’s stopping us, as Filipinos, to fully embrace grief? What will it take before our parents teach children, ‘it’s okay to cry” instead of pushing it back? For governments to acknowledge the gaps and prioritize community care? How many more of us have to suffer silently in the trenches?

Finding a return path

Whenever people in nonprofits deal with shadow work – tending to communities, working on the ground with COVID patients, for example – labor with effects often invisible to the naked eye, we enter a dark, difficult place. To go back to ourselves, we need to create a “return path.” A way to retrace our steps and resume the status quo.

But we can’t do this alone; when we jump into the abyss, we need other people to pull us back.

In other cultures, for example, the release of grief is an everyday, cultural practice. The Dagara people of Burkina Faso, for one, hold daily rituals to create safe spaces for hurt to be expressed and released. A person who has not cried in a long time is considered to be a ticking time bomb, seconds from imploding. Now, it’s the community’s role to facilitate their healing, so they can return to their life living more fully.

This expression of pain and grief is never shamed. In fact, it’s celebrated. “If we weren’t supposed to cry, would we have tears?” writes Sobonfu Some, author and ritual keeper of African tradition.

In contemporary times however, this could not be even more different. Sophy writes, “How is it in our modern culture? Perhaps a period of compassionate leave. What happens in that time? Often people find themselves isolated, as others continue with their occupations. Who calls in the ceremony, who shows up? I’m struck that even at funerals or memorial services there is often a wish “not to break down” and people may feel their tears are not appropriate or welcomed.”

Instead of releasing all the pent up grief and pain, we’re trained to push our natural impulses down.

So what can we do? What does it look like on the other side?

“We’re social impact workers, yes, but we’re also friends, daughters, sons, parents, fans – just people. “

“Welcoming each other with appreciation; giving gratitude to what is supportive or beautiful. Singing together, which supports the parasympathetic nervous system and releases the bonding hormone oxytocin, creating a sense of connection. Having down time, just to notice what is here – walking, sitting, reflecting with others, digesting the day, doing nothing but listening,” Sophy suggests in her article “Burnout and Grief.” “Acknowledging that we depend on each other and the living web of life for our existence. When we often notice what is good in life it is easier to give space to painful things that might make us pull away.”

I think, first, we need to build moments of silence in our daily schedules. A space to just take notice. Our body may be signalling pain, saying, “Hey, human – something is wrong!” but we instinctively bombard ourselves with noise, further alienating us from our own built-in emergency system. Sit down and reflect: where can I pause today? Who can I speak to? What is my body trying to tell me?

Now, the tricky part: building systems and processes, with the hope that it grows and slips into the mainstream. In your own circles and organizations, what return paths can you forge? What contemporary rituals can you instill in your way of work to normalize tending to burnout, grief, and other pain?

In makesense, we have a regular “Open Feelings Forum” twice a month. We realized team members may be feeling more and more isolated during the lockdown. So, we created a non-work space where we can listen to each other over Zoom. It allowed us to be honest with our struggles at home, with our connection with the cause. Thanks to our first few discussions, another habit was born: a regular gratitude practice.

For 10 minutes, we allow ourselves to celebrate our achievements. For such a fast-paced organization, we realized we’ve built moments to reflect on what we did wrong, but hardly any on what we did right. That had to change.

We’ve also added meditations to kick off some operations calls, from visualization techniques to breathing exercises. Personally, it’s a welcome reprieve; it signals an understanding that to show up at work as our best selves, we must care for one another holistically.

We’re social impact workers, yes, but we’re also friends, daughters, sons, parents, fans – just people. Just people.

What can this look like in our broader culture? What can happen when we realize the only way to create holistic radical change is to look at our struggles as a whole – the outer, the inner, what’s conscious, and unconscious? Maybe it’ll change everything. Maybe then we won’t have our impact-loving employees Googling articles on burnout so often – because they’ll be shaking off the shadows, already making their way back home.